Two Experiments of Arago (2022)

Two Experiments of Arago

An Unattainable Endeavor to Translate an Idea

Art residencies often claim to provide grounds for creating new artworks by granting the opportunity to live and work temporarily in a different environment. The fundamental premise of these programs is that, during the residency period, artists can enrich their body of work with the aid of novel ideas derived from exposure to diverse cultures. On the other hand, art residencies are in line with the idea of globalization, aiming to facilitate interaction among diverse artistic spaces. Nonetheless, the short duration of many art residencies appears insufficient to afford a substantial experience of the new cultures or even the locale. Furthermore, the limited duration of these residencies directs most artists towards seeking new ideas and attempting to translate them through the media in which they specialize. This solution resembles an approach known as “idea to execution”.

It’s important to recognize that “new ideas” serve diverse functions across different art scenes. For example, for artists working within the dynamic realm of Western art and capable of exhibiting their works through established art institutions, claims of art residencies focused on experiencing a new culture appear justified. The new ideas arising from this experience serve as a solution for such artists to transcend the confines of their body of work or to augment its facets. However, for an artist working, for instance, in the Middle East, the opportunity to experience a short-term art residency in Europe or the developed countries is more than just a novel cultural experience; rather, it represents a professional milestone. As a result, artists from such backgrounds often concentrate on perfecting their success during their residency, rather than expanding their scope of work. In simple terms, a Middle Eastern artist (or any nonmainstream artist) often aims to create work that appeals to a global audience, particularly targeting viewers in developed Western nations. This situation results in most artists working in such contexts leaning towards a relatively straightforward translation of an idea, rather than engaging in a long-term study for their work. Consequently, while the discovery of new ideas represents a deviation from the rigid body of work for Western artists, for nonmainstream artists, concentrating on such ideas often constitutes the main corpus of their work. Therefore, it can be argued that these “new ideas” highlighted in art residencies not only serve distinct functions across different art scenes, but also, simultaneously, act as stabilizing factors in solidifying this classification by steering artists from these two distinct backgrounds in separate directions.

Despite the typically short duration of art residencies, which equates to time constraint on artwork production, the limited presentation period can be seen as another factor enhancing the efficiency of the “idea to execution” approach. Put simply, this approach is often easily grasped by the audience, and typically, understanding the artwork only requires the artist to reference the personal or social context of the subject matter. This issue appears noteworthy since such interaction between the audience and the artwork is associated with another measure of success in nonmainstream art scenes: participation in international art fairs featuring the simultaneous presence of several dozen artists. In simple terms, an art fair attendee can establish a connection with the works during a brief tour of the exhibition by having some hints into the reasons behind the selected themes and subjects or by being familiar with the central idea of the collection. Thus, given the executive mechanism of art residencies and international art fairs, it seems that this approach is chiefly suited for the “success” of the nonmainstream artists. However, as previously noted, recognizing such outcomes as success contributes to reinforcing the boundaries and classification between different art scenes.

The current series has been produced with a focus on the limitations of “idea to execution” approach in a hypothetical art residency. The images of this series are conceptualized and photographed within approximately ten days at home, considering the limitations of the conventional art residencies. By staying at home instead of attending an international art residency, not achieving professional success has been accepted. However, this substitution is acceptable because it is assumed that gaining significant familiarity with a new culture is not feasible within such a short time frame. Nonetheless, it seems that the shortcomings of the “idea to execution” approach extend beyond the consequences of time constraints. Thus, this series seeks to address an additional limitation of such an approach by recreating the conditions of artwork production based on this framework: the impossibility of the translation of some ideas through artistic media. It is evident that the impossibility of translation does not imply the impossibility of artwork production; rather, it signifies that the available translation is significantly flawed and insufficient to fully convey the original idea. In this context, Two Experiments of Arago is a series of images that translate a simple yet critical idea through the medium of photography.

***

These photographs represent an effort to reconstruct two experiments conducted by Dominique François Jean Arago in the nineteenth century. During that period, it was still possible for an individual to simultaneously hold roles as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, and politician. Arago was one such character. As a photographer, we are likely first encountered to his name through his presentation of photography (the daguerreotype process) to the French Academy of Sciences.

Optical and photometric experiments were central to the studies and research of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. On one hand, diverse objective studies, such as darkroom experiments and astronomical observations, were conducted; on the other hand, dynamic and ephemeral experiences, such as the diorama and zoetrope, encompassed a broad spectrum of this field of inquiry. In addition to these objective experiments, other researchers, such as John Dalton, concentrated on optical studies involving human subjects, such as color blindness.

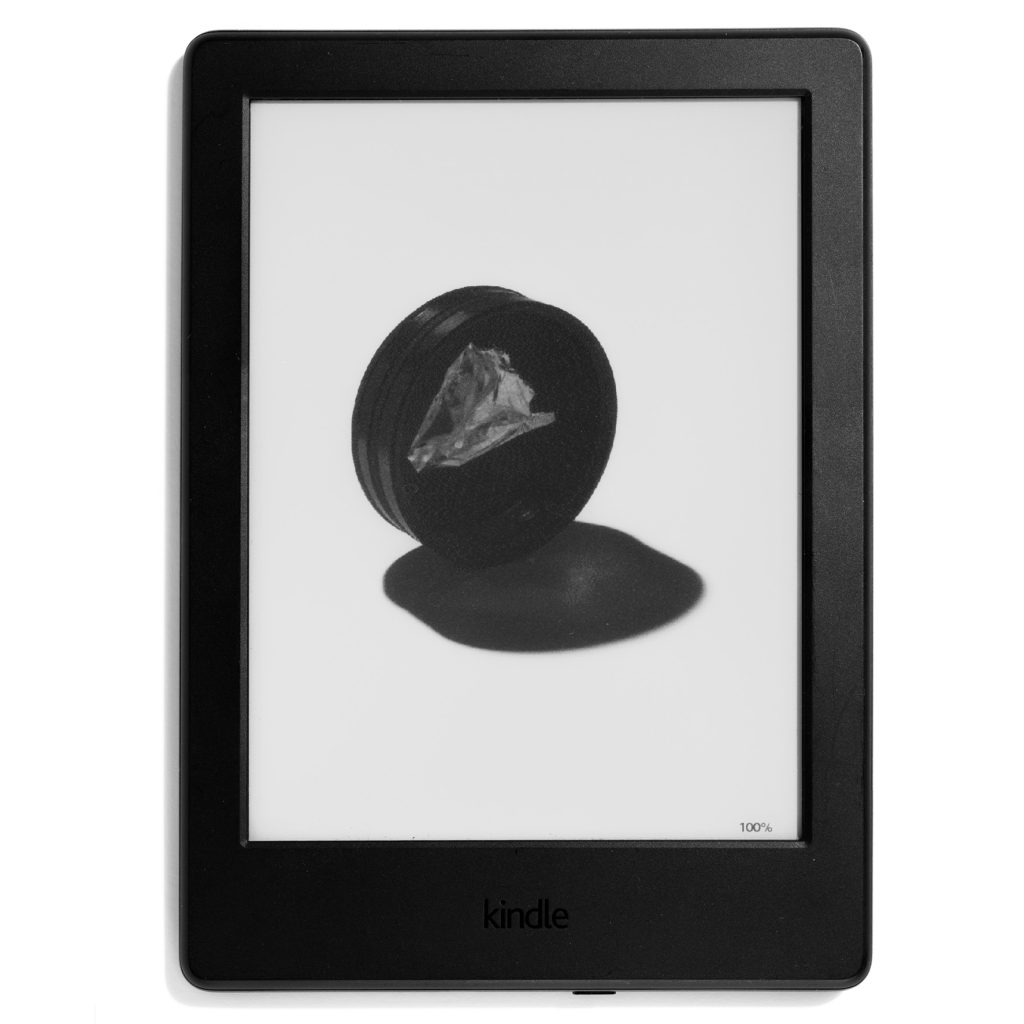

One of Arago’s experiments, recreated in this study, focuses on the change in light polarization as it passes through a transparent object. Arago, who invented the polarizing filter in 1812, subsequently introduced a device called the polariscope, which utilized two polarizing filters. Certain transparent materials, when positioned between these two filters, demonstrated alterations in brightness or color quality, with these changes varying as the object was rotated around the axis perpendicular to the filters. Although the visibility of this phenomenon might suggest that the experiment falls within the realm of objective studies, it should be classified separately from other early nineteenth-century photometric experiments due to its historical context. In fact, classical experiments in the field of objective photometric studies traditionally focused on the reflection and refraction of light. However, Arago’s experiment on polarization does not fit into either of these categories, as it involves obtaining color without the refraction of white light. Thus, such phenomena could not be justified by any of the photometric theories of the early nineteenth century. In other words, although reflection and refraction of light were well-established within the scientific framework of Arago’s time, his experiments on polarization fell outside this framework and even presented a challenge to it. Given these considerations, the first experiment in the present study focuses on the mechanism of the polariscope and seeks to replicate Arago’s pioneering experiment using two polarizing filters and several pieces of plastic.

Alongside Arago’s experiments, there were extensive debates concerning the nature of light, addressing fundamental questions that were not primarily focused on issues of light refraction and reflection. In 1818, the French Academy of Sciences, under the supervision of Arago, organized a competition to describe the properties of light as comprehensively as possible. Augustin-Jean Fresnel was among the participants who presented the wave theory of light. Siméon-Denis Poisson, one of the judges and an advocate of the corpuscular theory of light, sought to refute the wave theory of light, which had been proposed for about 150 years. Poisson argued that, according to the wave theory, a light spot should appear at the center of the shadow of the circular object. Since Poisson could not observe such a spot, he believed that Fresnel’s wave theory would be discredited. However, Poisson’s stance should not be viewed as antagonistic, as detecting this light spot in everyday experiences is practically impossible. Thus, although corpuscular theory encountered its own difficulties, the wave theory, despite its limitations, could not adequately replace it. To better understand Poisson’s claim, consider a scenario: imagine being in a vast, open space. In addition to yourself, there is a point sound source and a large circular or spherical object positioned between you and the sound source. If you are positioned behind the barrier and close to it, you will not hear any sound because there is no surface to reflect the sound waves. However, if you are positioned at a sufficient distance from the barrier, you will be able to receive the sound waves. This phenomenon occurs because sound, due to its wave nature, scatters as it passes the edges of objects. Conversely, if we replace the sound source with a light source, no light will reach any point behind a circular obstacle, as light travels in straight lines. Similarly, Poisson was confident that, by discrediting the wave theory of light and in the absence of a significant alternative, the corpuscular theory, despite its issues, would continue to stand strong.

Arago, who had previously conducted significant experiments on the polarization of light, believed that polarization was only plausible if light possessed a wave nature. Consequently, he sought to examine this light spot with greater precision. He found that this phenomenon could be observed on a small scale. In an experiment using a black object with a diameter of two millimeters, he was able to detect the light spot. This occurrence is explained by the concept of diffraction. Interestingly, in scientific circles, this light spot is known simultaneously as the Arago spot, the Poisson spot, and the Fresnel spot. Furthermore, in Arago’s experiment, diffraction exhibits another characteristic: distinct bands of light emerge as waves around the object’s shadow. Similar to the Arago spot, this phenomenon does not manifest in everyday experiences or in the shadows of large objects. This behavior is particularly evident when the experiment is conducted using limited frequency (monochromatic) light. Thus, the second experiment of the present study concentrates on two manifestations of diffraction observed in Arago’s experiments: the light spot and the wave-like fringes of dark and light bands. This experiment is conducted using monochromatic radiation (laser).

The relative simplicity of Arago’s experiments today might lead one to consider the experiments in this photo series as recreations of his work. However, there are fundamental differences between the two. For instance, it is crucial to note that during Arago’s experiments, photography had not yet been invented. In fact, physicists would have had to wait at least a century before a camera could effectively document these phenomena. Therefore, while photographing relatively simple experiments like these may seem trivial today, producing such visual documentation during Arago’s time was impossible. This is especially significant for the light spot experiment, which is not easily replicated, as Arago could not provide visual evidence for his findings. The absence of such images is also evident in Fresnel’s letter to Arago regarding biaxial birefringence. In the letter, Fresnel writes, ” I have checked several times the direction of polarization of the fringes, so that I am perfectly sure of this result.” He further requests that Arago, given the possibility of concurrent experiments by other scientists, share the descriptive results of his experiment with the Royal Society of London, if feasible. As these correspondences reveal, the credibility of such claims was assessed not through visual documentation but through the speaker’s reputation, precision, and honesty. This context underscores the significance of Arago’s advocacy for the patenting of photography at the French Academy of Sciences.

Beyond the ability to document these experiments, a fundamental distinction between Arago’s era and the present day introduces a profound gap between his original experiments and their contemporary recreations. The issue is that, in the early nineteenth century, physicists still believed that space was filled with an infinite, invisible matter known as the luminiferous aether. This belief was crucial because any of the corpuscular or wave theories required a material medium. The phenomenon of light polarization further demonstrated that light exhibits transverse vibrations, waving perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Since transverse vibrations can only exist in a solid medium—which, unlike liquids and gases, resists any deformation—the luminiferous aether was presumed to possess properties analogous to those of solid matter. However, in this case, planets and stars, situated within a space filled with luminiferous aether, would not be able to move. Consequently, given the prevailing knowledge of physics of Arago’s time, his experiments on polarization posed a problem that was either inexplicable or, at the very least, problematic for him. Nevertheless, Arago’s findings on light polarization and his observations of the light spot led him to support the wave theory of light. In contrast, it is not difficult for us today to conceive of a space completely devoid of matter that still permits the propagation of light.

To evaluate the wave theory, Arago devised an experiment to measure the variation in the speed of light across different materials. Accepting the wave nature of light, it was anticipated that, analogous to sound, the speed of light would increase when transitioning into a denser medium. In 1838, Arago outlined a device designed to measure changes in the speed of light across different media. But due to the political turmoil in France during that period, this concept was not tested until 1850. However, before these experiments could be concluded, Arago lost his sight. Nonetheless, prior to his death, it was proven that the speed of light decreases in denser media, contrary to Arago’s expectations and those of other proponents of the wave theory.

Thus, although Arago’s experiments on the polarization of light and the light spot were consistent with the wave theory of light, his other experiment refuted this theory. Arago’s experiments significantly intensified the crisis in the knowledge of optics of his era, making all prevailing theories appear inadequate. Ultimately, in 1864, James Clerk Maxwell offered a more accurate explanation of the nature of light with his theory of electromagnetic waves, which remained largely unchallenged for several decades.

The scientific contradictions in Arago’s experiments, arising from the period of scientific turmoil in which they were conducted, preclude these experiments from being categorized as objective tests in the field of optics. In contrast, contemporary experiences —pleasant, easily accessible, and readily documented—can be readily categorized as objective experiments. It seems that the experiments of the early nineteenth century cannot be replicated simply through repetition. Given this, how can such experiments be documented and presented to an audience through photography if they cannot be faithfully recreated? To put it differently, if the primary aim of this series is to recreate two of Arago’s experiments, how can photography offer a suitable translation of this concept? One potential answer is that these photographs, captured with a conventional camera, may be viewed as a form of documenting the “experiments.” Indeed, this form of representation is so explicit and literal that its authenticity is difficult to challenge. However, given the fundamental gaps identified, it cannot be regarded as a translation of “Arago’s experience” into the medium of photography; instead, these are merely records of “Arago’s experiments”. As previously mentioned, the impossibility of a perfect translation does not imply the impossibility of producing a work; rather, it indicates that the translation will inherently possess significant and unavoidable shortcomings relative to the original idea. This conclusion can be articulated using established terminology from the field of photography: the two recreated experiments in this series should be considered as staged representations of Arago’s investigations.

***

It seems that images without human subjects are more suitable for studying the mechanism of photography, as human subjects frequently prompt a range of interpretations across different disciplines of the humanities. Today, photographs of everyday cultural objects also exhibit this characteristic due to their connection with humans. However, while the images in this series are devoid of human subjects and everyday objects, which complicates deriving interpretations related to the humanities, multiple divergent interpretations may still arise when engaging with these images. For example, such visually compelling images may readily be subjected to formal interpretations or worse, abstract engagements. I am confident that the photographs of this series do not prompt reflections about us, our memories, death, society, the environment, etc. which I find agreeable. Moreover, I am pleased that these images cannot, in any way, be categorized within the domain of narrative photography.

As previously mentioned, this series was created to examine a critical aspect of the “idea to execution” approach. In this regard, the recreation of scientific experiments serves as an illustrative example of a simple yet critical idea. In fact, the primary goal of this study is to provoke questions about photography itself, rather than about optical issues, through the documentation of these scientific images. For example, one might question whether scientific images can enhance our understanding of photography itself. To which side of the renowned binaries of photography_ mirror/window and document/image_ do these images gravitate? Do these images serve as documents in the same manner as news photographs are perceived? Can such images be integrated into the artistic domain, or, more precisely, can this book be classified as an artwork or a photobook? On the other hand, can studying a scientific archive of this kind provide insights about the relations of photography, analogous to what is learned from examining police, news, family, or other types of archives?… Numerous additional questions could be raised concerning this series; however, its primary focus is on the following question: Can the translation of a straightforward and simple scientific idea into these images serve as the subject for a critical approach to photography, thereby elucidating aspects of the photographic medium’s mechanism?

Engaging with such questions is important because it relates to the mechanisms by which unconventional images are incorporated into the realm of art. By analyzing images from unconventional domains, such as family albums and scientific photographs, which have been incorporated into exhibition spaces or photobooks, one can observe that these images frequently convey meanings that extend beyond their subjects. For example, many old photographs, especially those portraying human subjects, enter this domain due to their nostalgic qualities or anthropological relevance. Likewise, certain documentary images are featured in exhibition spaces because of their formal attributes or the long-term study of a particular subject. But what else can scientific images _ as already noted_ without human subjects, which attempt to engage objectively with their subject matter, signify beyond their subject? One potential answer to this question can be examined through the process of recreating these scientific experiments and translating them via the medium of photography.

In instances where a series is developed according to the “idea to execution” approach, the attainability of the idea is typically assumed, and the producer regards the resulting works as evidence supporting this presumption. Given the above, the representation of Arago’s experiments remains at least twice inaccessible to the audience: first, due to the impossibility of replicating the original experiences, and second, due to the inherent limitations of photography in accurately representing any external subject. Thus, although the concept of executing a straightforward idea, such as recreating a scientific experiment and representing it through photography, may seem readily achievable_ and images can be presented as representations of these experiments or, alternatively, as “photographic executions” of them_ this idea, in practice, proves to be attainable. Consequently, the effort to “execute such an idea,” despite having such a book, remains an unattainable endeavor.

However, as this series illustrates, the unattainability of the idea does not equate to the impossibility of presenting works related to it. In this context, the concept of “translation” can be used for a better understanding of the subject. The images presented here serve to represent the central idea of the series (Arago’s experiments); this is analogous to translating a precise and nuanced concept into generalized terms and phrases that only partially correspond to the original subject of the translation. From this perspective, while the inaccuracy in translation may arise from the inability of the translator (or artist), it is also possible that the idea or concept itself may be inherently resistant to translation. Therefore, it is anticipated that the assumption of attainability in the “idea to execution” approach should be critically examined and reassessed.

Now if we, simultaneously, examine the critiques of art residencies, international art fairs, and the “idea to execution” approach, it becomes evident that nonmainstream artists often select a highly restrictive approach in the hopes of achieving professional success. On one hand, the artist encounters constraints such as the brief time available for developing a topic and the narrow range of subjects that can be explored within this short period. On the other hand, the inherent deficiencies of this approach often lead to the artist’s intended concepts being conveyed to the audience in a highly generalized manner. Thus, what is predetermined by the global art scene for the nonmainstream artists often leads, in a complex manner, to the reinforcement of the very classification to which they belong. (Written by Roozbeh Maleki, Translator: Niki Shadloo)